|

Partially secluded by the lush surroundings of Jalan Dato’ Onn, lies Sasana Kijang, a spectacular building that houses Bank Negara’s extensive art collection. Many of us were rendered speechless at having discovered one of Kuala Lumpur’s hidden gems.

Once our annual general meeting was completed, we were privileged to have Director of Bank Negara Museum and Art Gallery Lucien de Guise, talk to us about collecting Malaysian art. Lucien has lived in Malaysia for more than 20 years, but since his recent return to the UK, divides his time between both countries, enjoying the best of both worlds.

Lucien studied Islamic History and Art at the University of Oxford in the UK. He joined the newly opened Islamic Arts Museum in KL in 2004, before moving to Bank Negara Art Museum in 2015. His interest is not confined to Islamic art however, and his broad and in-depth knowledge of contemporary art formed the basis of an informative lecture. |

|

We were introduced to the work of Contemporary Artist Chang Fee Ming, whose paintings have been exhibited around the world, and sold through prestigious auctions at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. The unparalleled complexity of Malaysian culture is intricately woven throughout his work and depicts what Lucien believes, is the true meaning of 1Malaysia. The elements of nature entwined with rural living feature predominantly in much of his work, and we were not surprised to hear that these highly collectible pieces are in great demand, making Chang Fee Ming the hottest name at Malaysian auction houses.

It was a revelation to many of us, however, to learn that auction houses are relatively new to Malaysia, the first auction taking place at Henry Butcher Art Auctioneer in 2010. Three other major auction houses have since opened in quick succession: The Edge Galerie, KL Lifestyle Art Space, and Masterpiece Auction House. These public auction houses provide a transparent platform from which the public can ascertain the benchmark for the price of Malaysian artwork as well as encourage collecting and investment.

Before the introduction of auction houses in Malaysia, art enthusiasts would visit galleries with a keen eye for investment. Unfortunately, galleries are not doing so well and it is becoming difficult for buyers to form a relationship with artists. Furthermore, exhibitions appear to be on the decline and it is difficult to find out about upcoming events because information is not sufficiently publicized.

The National Art Gallery and Petronas Gallery both exhibit some of Malaysia’s finest art for public viewing. Malaysian Airlines and Bank Negara both own impressive collections, but unfortunately, the majority is not accessible to the public; Lucien tells us that only about five per cent of the paintings owned by Bank Negara are displayed. Furthermore, the lack of government and private galleries mean the opportunity to view art is severely limited.

Lucien explains that in other countries such as the UK, Korea, Japan and Turkey, prominent art collectors show their vast collections to the public at private exhibitions. He cites The Charles Saatchi Gallery as an example. This prestigious private gallery of contemporary art occupies 70,000 square feet at the Duke of York Head Quarters in Slone Square, London. Its philosophy is to show contemporary work that would not otherwise be seen in institutions such as the Tate Modern, thereby providing a platform for unknown artists, as well as making art more accessible to the mainstream. It attracts 1.5 million visitors per annum, and admission is free! At present, there is nowhere in Malaysia to view private collections on this scale because either collectors haven’t acquired enough art, or they are unwilling to display it.

The acquisition of art seems to be dominated by a small circle of collectors, some of whom collect art out of patriotic duty or purely for investment purposes; many are foreigners, perhaps diplomats or businessmen who purchase paintings during their stay and take them home when they leave … unlike many countries, there is no export restriction on art in Malaysia. Naturally, there is a keen interest in purchasing national treasures by artists such as Latiff Mohidin, Ahmad Zakii Anwar, Jalaini Abu Hassan, and of course, Chang Fee Ming. As long as collectors keep buying, the prices will keep rising; as Luicen says, once you make it as an artist in this country, you will keep making it.

So where should those with a moderate budget go to find Malaysian art? Lucien suggests we get online and check out the auction houses, because we might be pleasantly surprised to discover some fabulous pieces at relatively cheap prices. He encourages us to keep our ear to the ground and regularly check the press for information about art exhibitions and events. The problem, he tells us, is that there is no platform for young artists to get their work out there.

There have been several attempts to showcase unknown artists: Up For Grabs, a bazaar that sold a wide range of art at reasonable prices caused a temporary buzz in the art market, but Lucien says this event withered to little more than a book fest. Another rather novel event involved artwork by unknown artists being offered for sale alongside work by famous local artists. However, the identity of the artists were not disclosed and prices were kept within a similar range so buyers could choose their favorite pieces without prejudice … and perhaps unwittingly purchase a famous masterpiece at a knock down price! Disappointingly, such events have only achieved marginal success, and it is uncertain whether this is due to lack of interest or because advertising and marketing is not filtering through to the right audience.

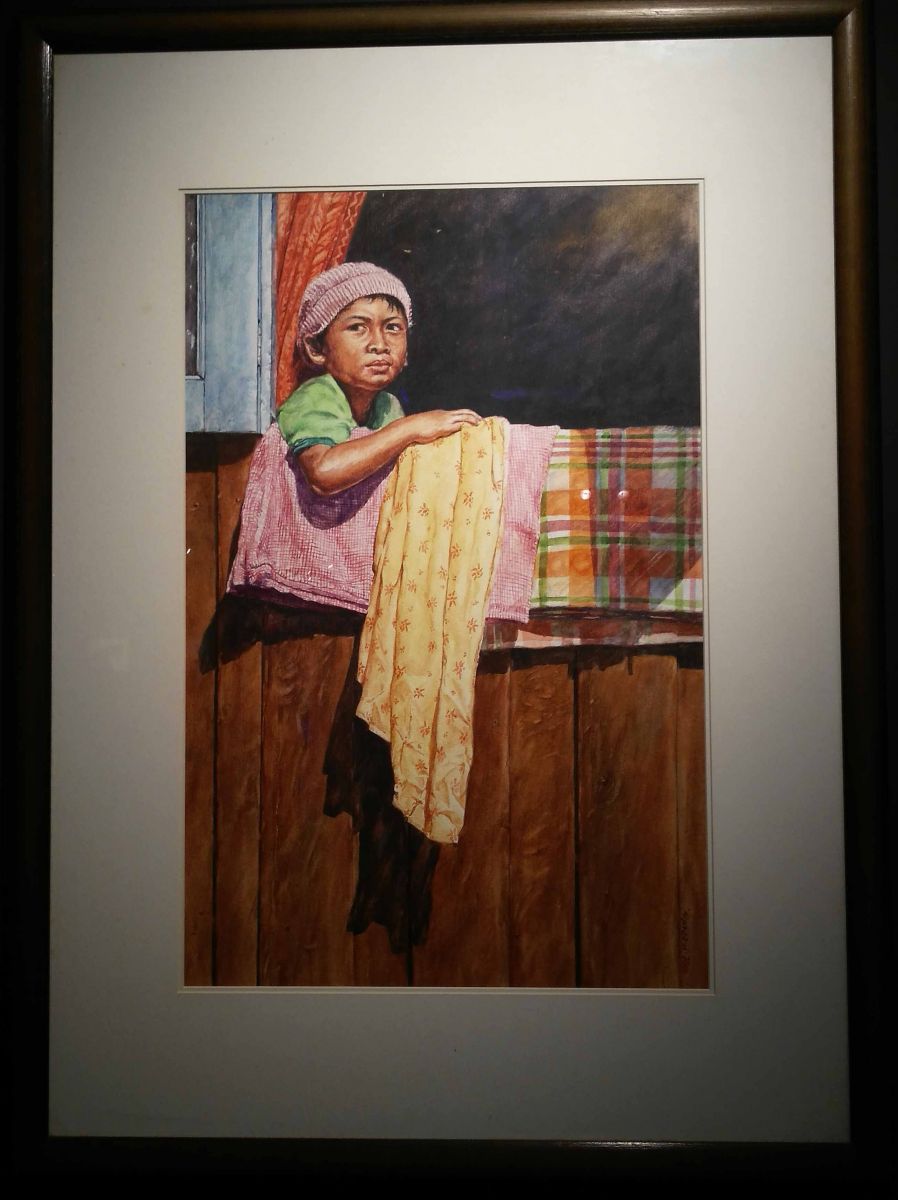

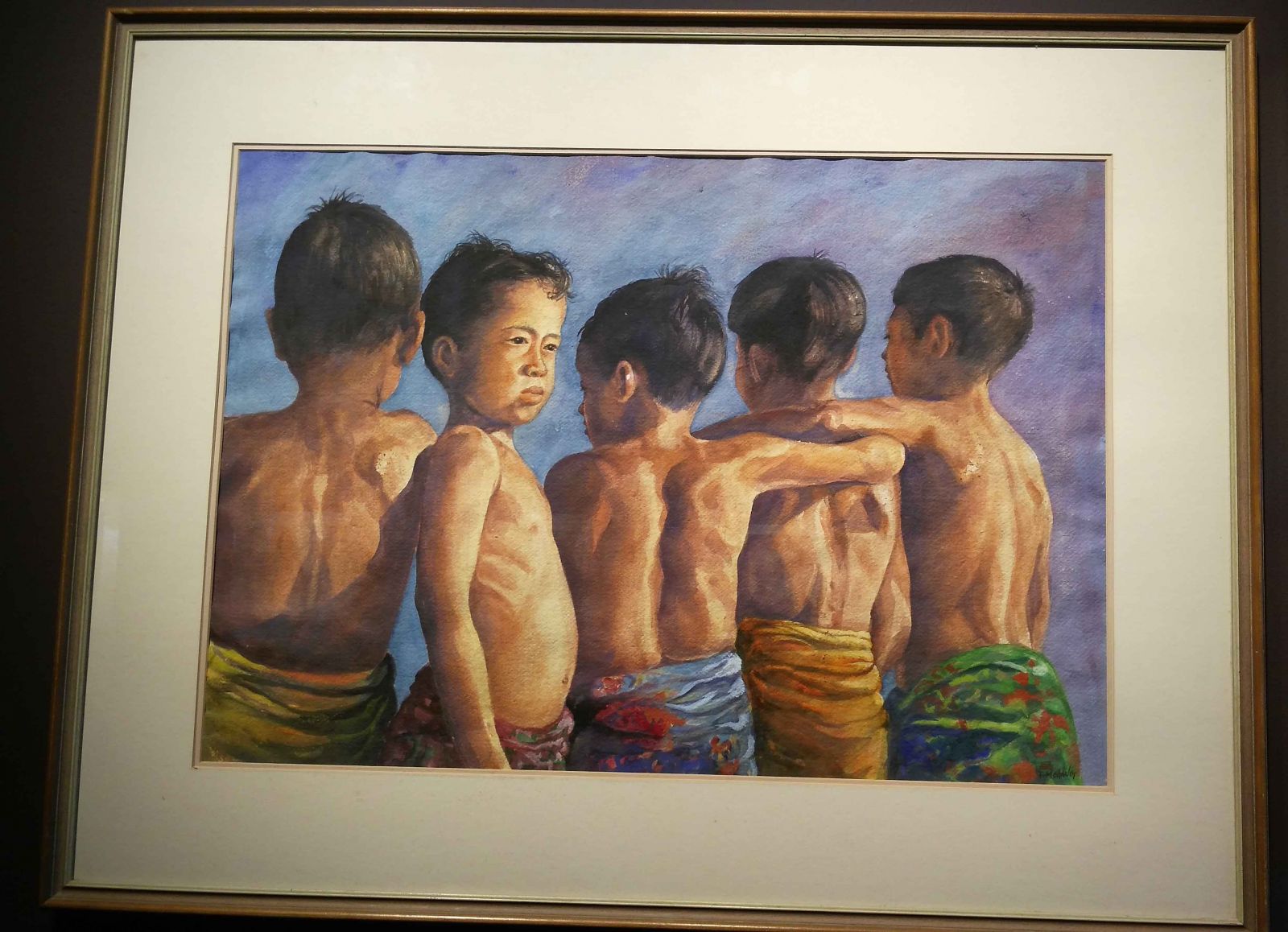

There is no doubt that Malaysia has an impressive pool of highly talented artists, and auction houses have helped to drive interest by providing a secondary market through which they can show their work to collectors. Nevertheless, young and unknown artists are still struggling to make their mark on the local art scene. Interesting, foreigners account for a substantial proportion of collectors, and their input is crucial to keeping the Malaysian art market buoyant. Lucien feels that there needs to be cooperation between various organizations to establish a platform for unknown artists so they can get the exposure and recognition that they deserve. The Malaysian Culture Group is one such organization that takes a keen interest in local art, often promoting it through lectures and excursions. As the lecture draws to a close Lucien acknowledges the important role that the MCG plays in promoting local artists and, with that thought to ponder, he leads us up to the third floor to view the much anticipated Chang Fee Ming exhibition. On arrival, we are greeted by Deputy Director Tunku Mariati Mukhtar, who tells us a little of Fee Ming’s background. Born in the small town of Dungun in Terengganu in 1959, Fee Ming is a self-taught artist whose career started in the early 1980s. His thought-provoking compositions, vibrant colours and exquisite detail have become his trademark, making him one of Asia’s finest watercolour artists.

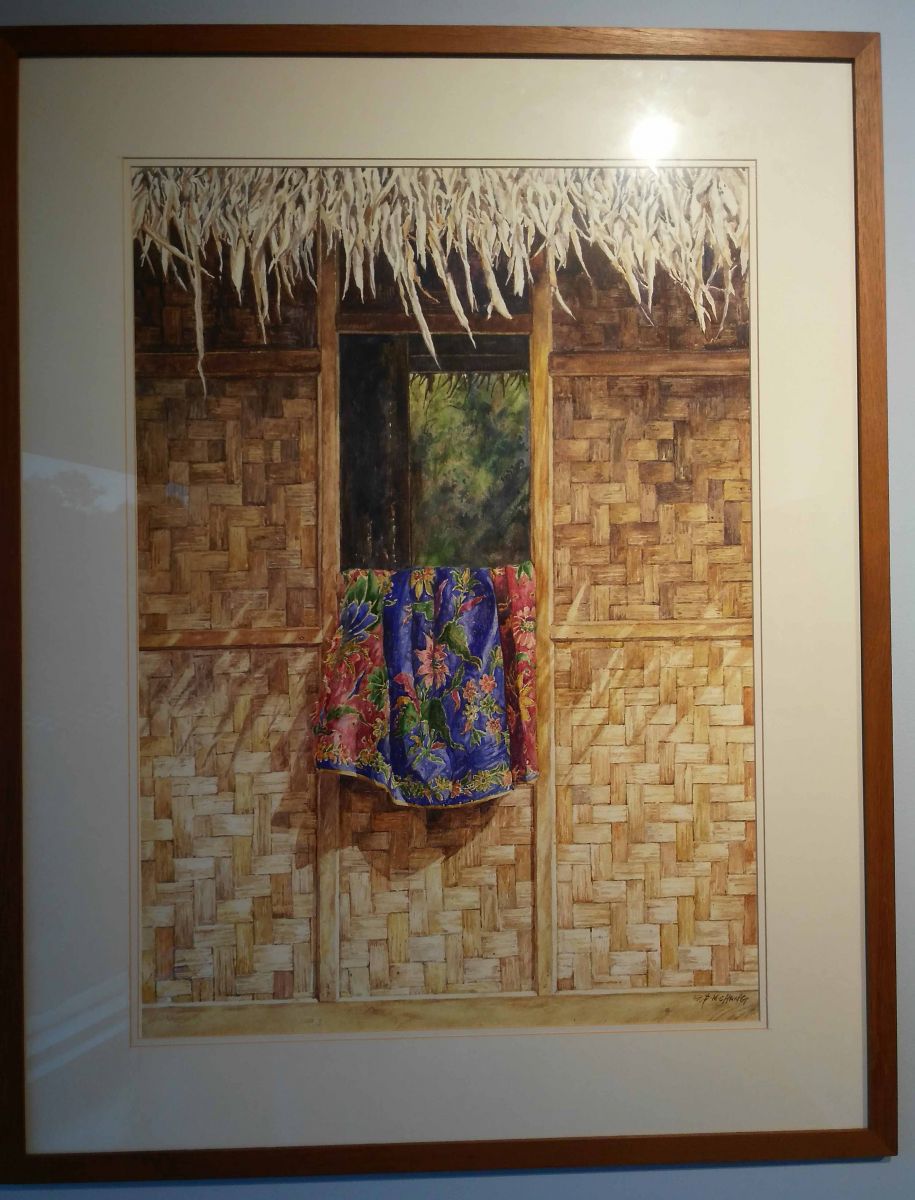

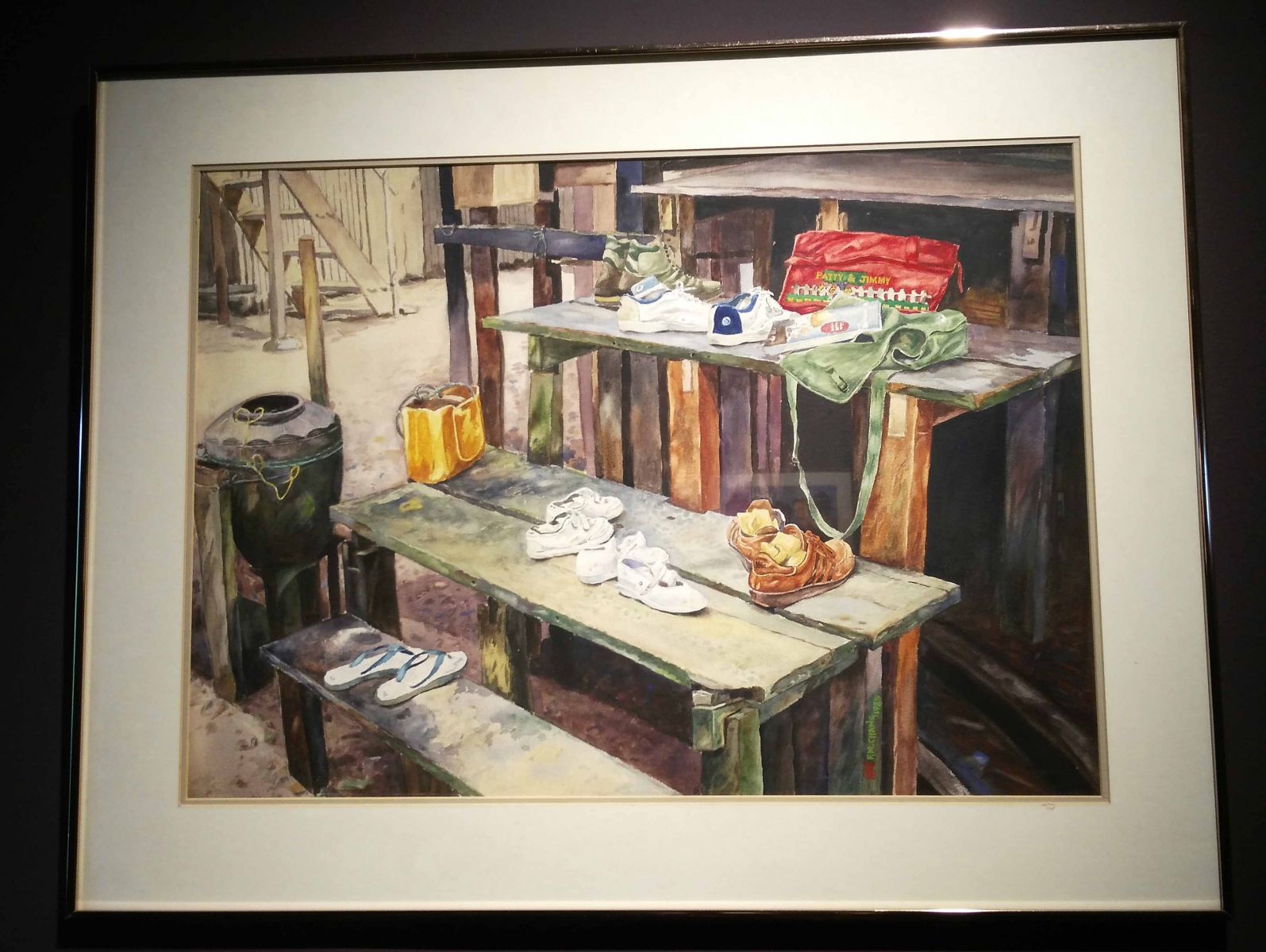

Fee Ming’s earlier works feature mainly landscapes and are what you might expect from a traditional watercolour painting: loose strokes, translucent colours and a vague background. But as he progresses, his technique changes: watercolour is heavily layered resulting in a vibrancy typical of oil paint; indeed, at first glance, his work can easily be mistaken for an oil painting. His composition also changes as he turns his attention to detail, homing in on specific aspects of life in the Malay kampong.

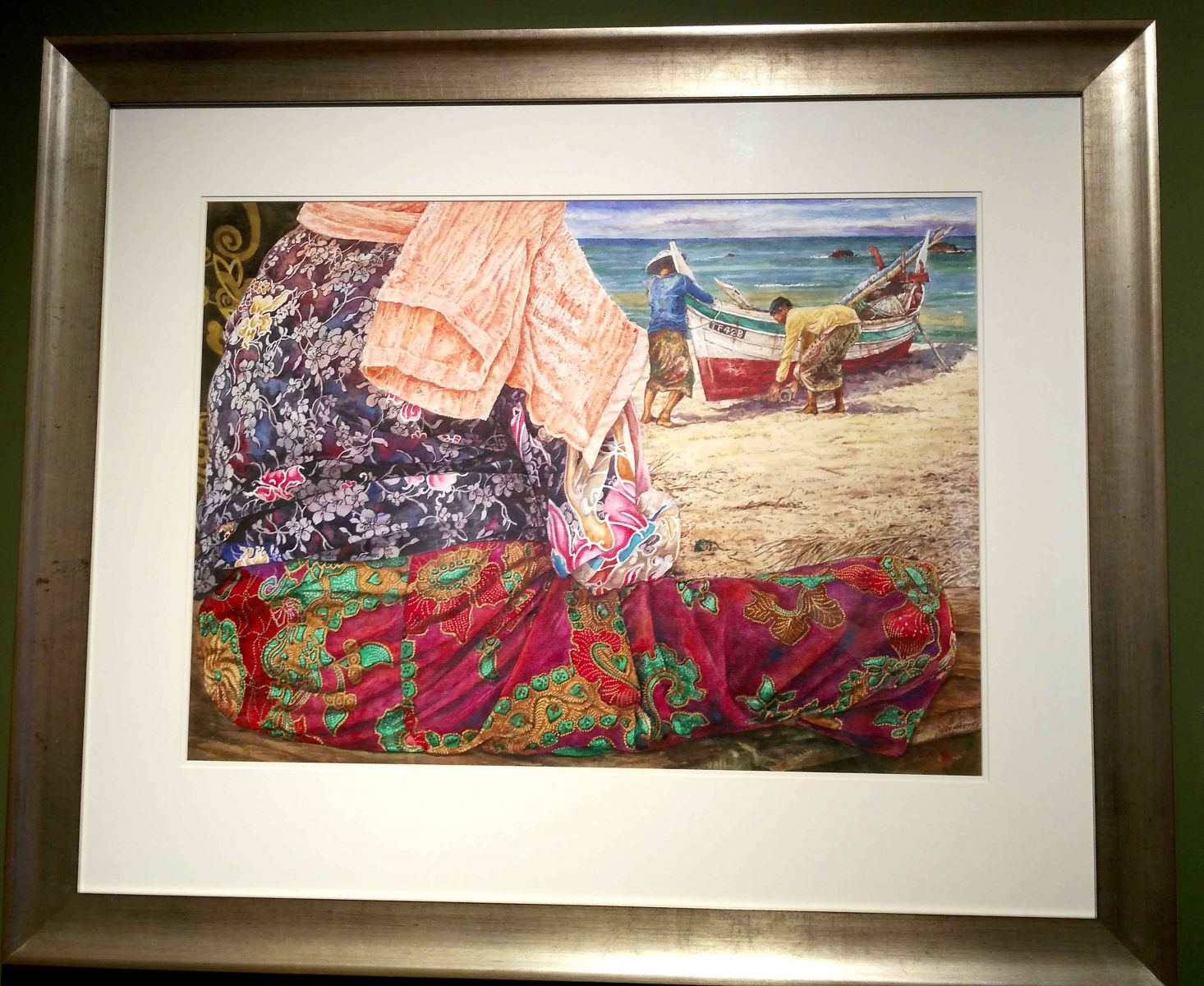

He has the most extraordinary talent for capturing the sentiment of village life; observing simplicity, beauty and hardship in the same composition. This is beautifully depicted in the painting Arrival & Departure, in which a woman stands on the shore watching the fishermen pushing their boats out for the day’s catch. As is typical of Fee Ming’s compositions, the identity of his subject is withheld: the woman in the foreground is viewed from behind, cropped from shoulder to thigh so we notice the detail of her sarong; the tension in her posture; the angle of her strong arms and the way in which her capable hands grasp her hips. In the background we can see the fishermen from the elbow down, but their powerful movement leave us in no doubt of the toil that lies ahead. In the second part of the painting, it is the fisherman that occupies the foreground, watching the women assemble to take charge of the arriving boat. The subject is similarly cropped, but we know from the drape of his sarong that he is spent, yet satisfied with his catch.

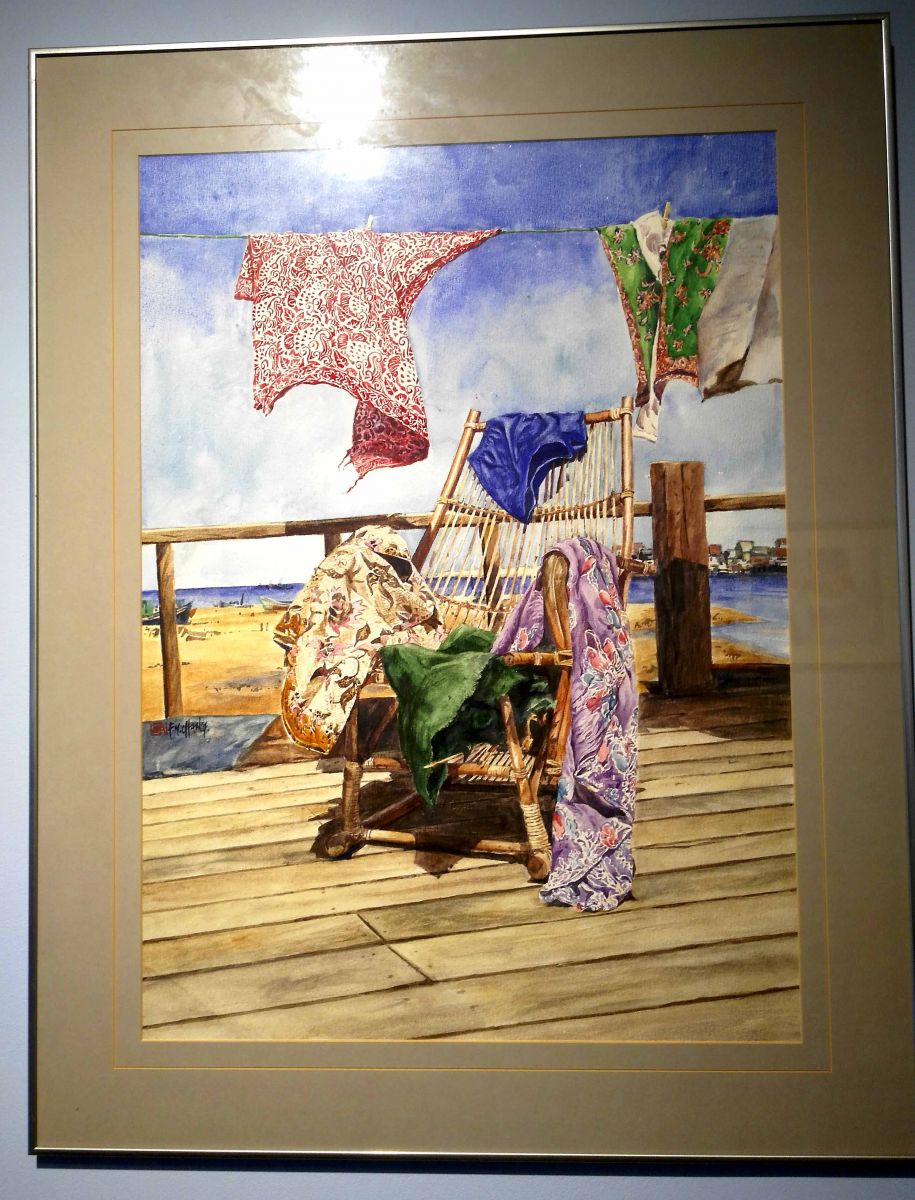

Fee Ming’s affinity with fisherfolk is evident in many of his paintings: fishermen hauling boats from the sea; women gathered around the day’s catch; a child squatting on the beach examining a solitary fish; reels of fishing tackle held by a sun-scorched hand; sarongs blowing in the wind; villagers sitting in quiet contemplation.

His appreciation of women is also apparent as he draws our attention to their strong shoulders, wide set hips, swollen ankles, and chafed hands. Sometimes the women are absent in the composition, but their presence is felt as he zooms in on the family home: freshly laundered clothes hanging on the veranda; a pile of neatly folded bedsheets; a rolled up mattress and bolster balancing on the window ledge; a child’s sandals placed on the doorstep; a basket of fresh vegetables awaiting preparation.

Although faces are often obscured or completely cropped from a composition, they sometimes form the most captivating focal point. Fee Ming paints with incredible precision, celebrating the aging process in every line, wrinkle and feature: an elderly man looks out to sea, his skin weathered from a lifetime’s exposure to the elements. We wonder what he’s thinking as his eyes shine with memories spanning three, perhaps four, generations. Life in the Kampong thrives on close extended family and strong neighbourly ties, and this is eloquently depicted in Letter to A Son, in which a father writes a letter to his son whom we presume is studying overseas. Painted in 1985, the scene captures a sense of excitement and anticipation as family members gather in the plantation to discuss local news, while a young man puts the proud father’s communication into words.

This wonderful exhibition brings together the colour and charm of Terengganu, with a delicate interplay between cultural traditions and deep-rooted family values that are characteristic of Malaysia. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We thank Lucien for taking time out to acquaint us with the work of Chang Fee Ming, and several other Malaysian artists, especially given that he had just arrived from the UK the previous day! Despite feeling jetlagged, Lucien delivered an interpretive and enlightening lecture from which we have gleaned a clearer understanding of the local art scene and the future of collecting art in Malaysia.

Chrissie Kemp |

|