|

MCG Trip to the “Valley of Hope” Sungai Buloh Leprosy Museum and Settlement

Monday, 13/05/19, 10.30am, tour guide Dr. Faizah

|

|

Back in the 1920’s leprosy was still an incurable disease, patients hid from the view of the world and lived as outcasts, stigmatized by society. In 1926 the British Colonial Government established the Leprosy Enactment Act to bring the spread of this disease under control by enforcing compulsory isolation of the leprosy patients.

As a result of this Leprosy Enactment Act the Sungai Buloh Settlement was established in 1930, a highly-organized and well-equipped leprosarium with a modern hospital, schools, residences, houses of worships, clubs and halls. It also had a market, laundry, shops, police stations, and even a prison. Mostly unknown to the public, it once used to be the second largest leprosarium in the world, situated in a beautiful scenic setting just outside the Kuala Lumpur city borders, where patients felt hope for cure, therefore the name “Valley of Hope”.

We met our tour guide and NLCC (National Leprosy Control Centre) medical officer Dr Faizah Abdul Ghani at the “Valley of Hope” Communal Hall. Coming straight from her practice at the hospital, Dr Faizah started the tour in the museum building where we learned about the history of the leprosy disease and the “Valley of Hope” patients. At the beginning there were 2,000 settlement inmates (80% Chinese, 10% Malay and 10% Indian origins), while the current number has gone back to 116 with the youngest patient being 60 and the oldest patient being 93 years old.

|

|

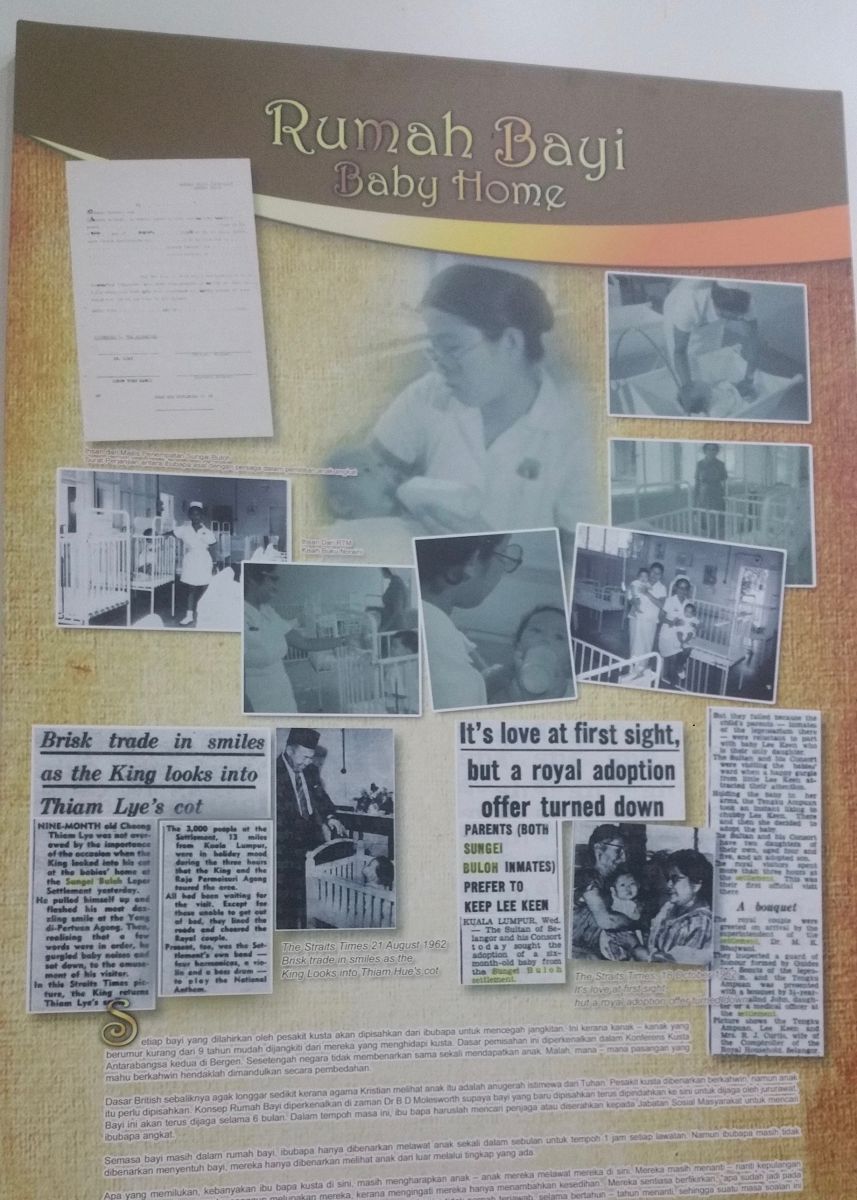

The first settlement building was erected in 1926 with the aim to give each patient their own “chalet”, a one room hut with a bed and storage for personal belongings like their own cooking utensils. Patients are encouraged to be involved in rehabilitation activities such as gardening, rearing chickens and re-building their own limb prostheses. In the old days, the inmates used to cook their meals together during the day. When patients got married they possibly lived together in one chalet, but very sadly, when children were born to these inmates, they were taken away from the parents and put up for adoption. Today, there are efforts by a group of engaged people to support those once adopted children in finding their original parents by means of a database which can be accessed on the internet.

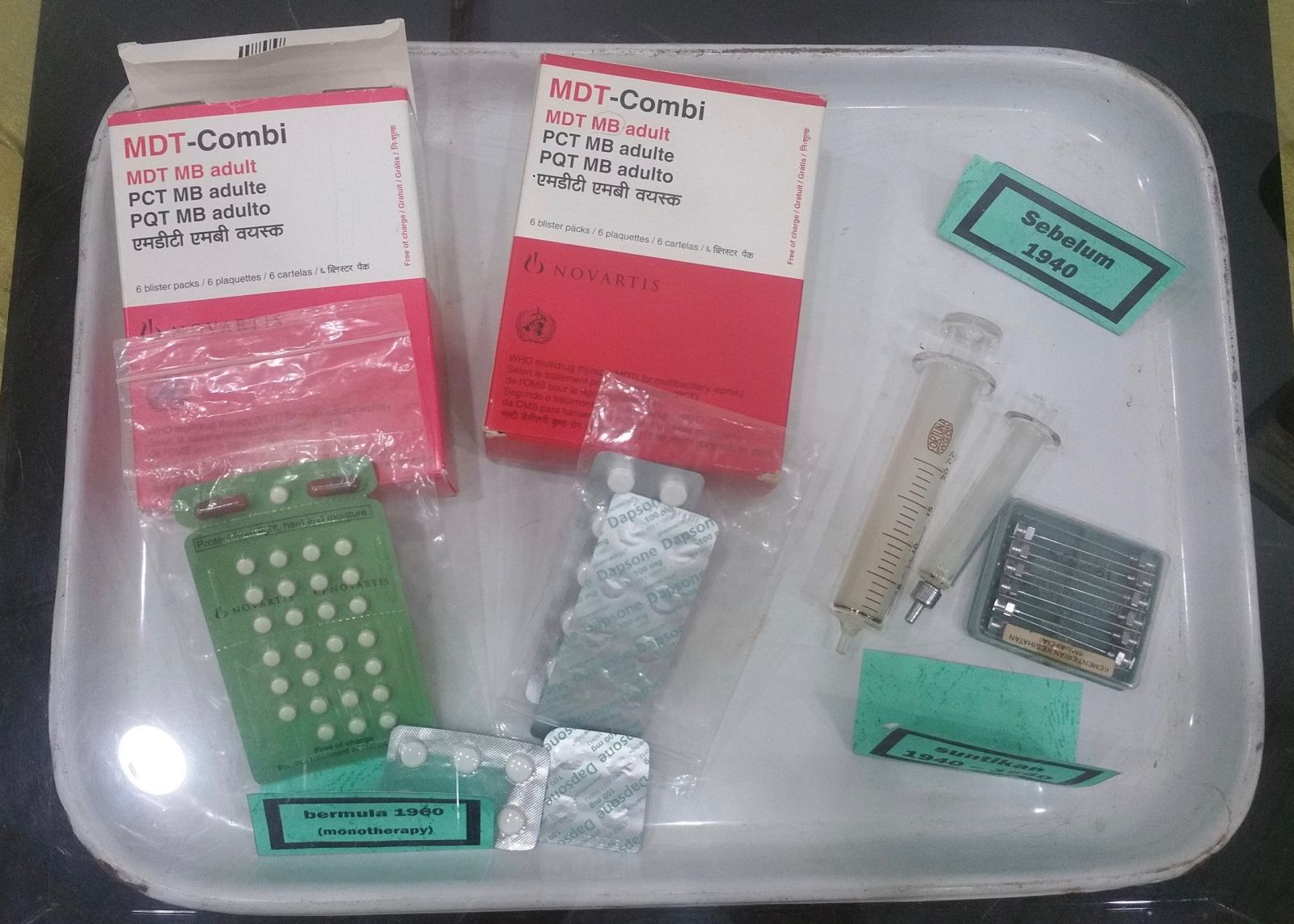

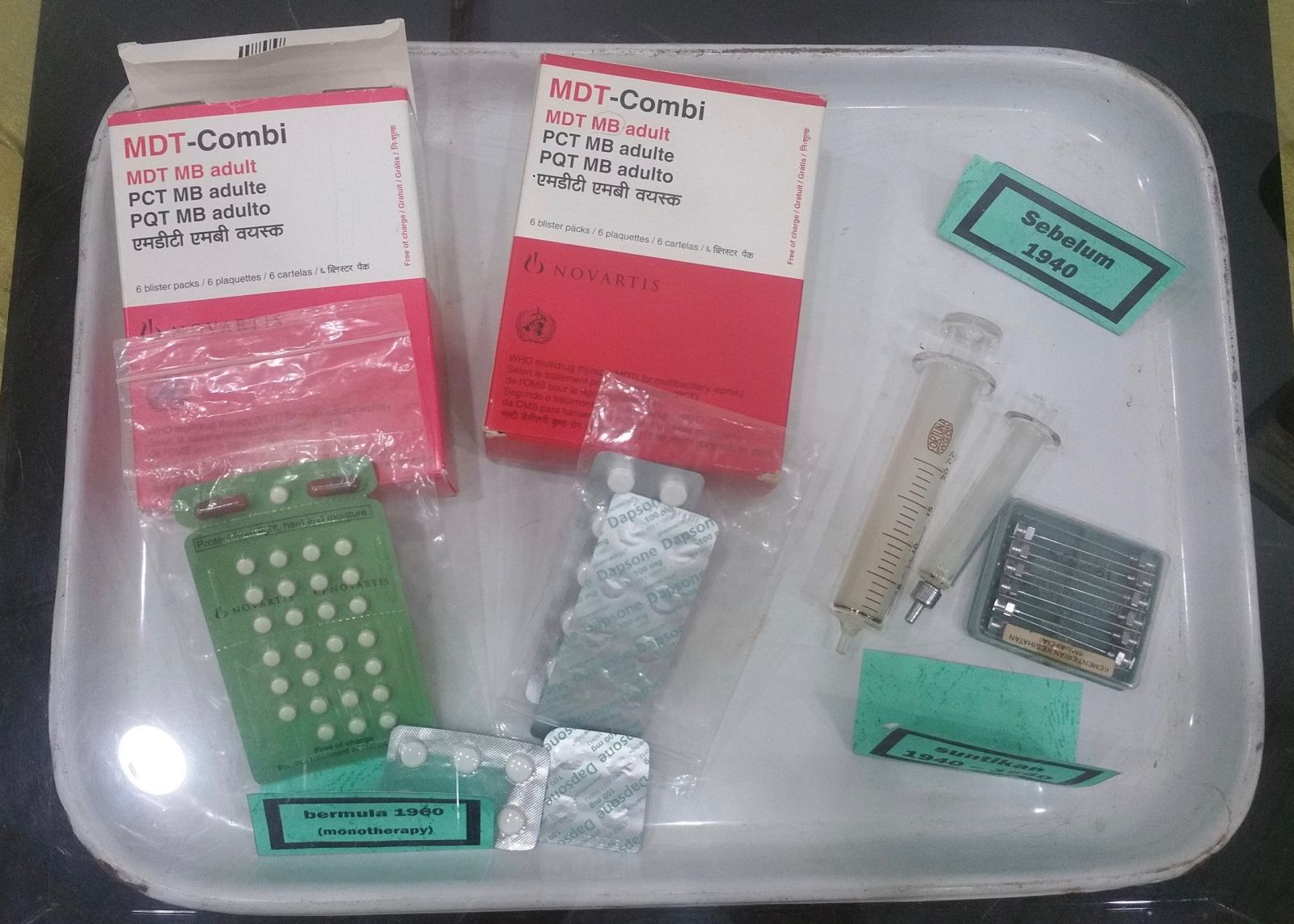

Apart from Dr Faizah’s information for this building there were displays of paintings of the previous doctors, history timeline, medical instruments, pills, old maps of the settlement and many more artefacts related to the disease.

Afterward we visited the gallery building with equipment for physiotherapy and prostheses, some of which were made by patients themselves. These together with occupational therapy helped to get their life functioning as for any other normal person.

The leprosy disease spreads by nasal secretion or droplets, however close and long period of contact is needed with the infected person. Incubation period can be from a 3 months to up to 20 years, during this time leprosy is commonly misdiagnosed and left untreated. Important signs of infection to look for are non- itchy hypopigmented skin patches with sensory loss. Nerve damage is the most characteristic feature of the disease, and is also the main cause of the disability suffered by the patient. It characteristically removes the sensation of pain, therefore the patient is prone to hurt and to deform himself. Secondary infections, in turn, can cause tissue loss, resulting in fingers and toes to become shortened and deformed, as cartilage is absorbed into the body. While early detection can heal the disease, deformities may not be reversed.

|

|

Slit Skin Smear tests can be done at leprosy centres or any government dermatology clinic, but due to this being painful it is not common that people choose to be tested unless symptoms occur. In the course of our tour we passed the laboratory building where those tests were being read.

Due to new laws in the 1960’s, patients were not supposed to be isolated any longer and the settlement was opened so the inmates were free to leave and go wherever they chose. While a number of patients left the settlement, others chose to stay as they did not have a place to go with no more family members outside the settlement left or simply because after all these years the “Valley of Hope” had become their home. But at that time the society was not ready yet, and people were still afraid to mingle with leprosy patients and further stigmatizing them.

The leprosy bacterium has been found in few animals only, one of which is the armadillo; their low body temperature is very hospitable to the leprosy bacteria, although monkeys, mice and rabbits can contract it as well. So opposite of the laboratory building we passed the so-called “Rat House” where research on rats had been conducted in search of finding a leprosy medication.

|

|

In 1969, the Sungai Buloh Settlement was officially designated as the National Leprosy Control Centre in Malaysia, a centre of research for trials with “Dapsone”, the only existing medication at that time, and later working together with the British Medical Research Institute in London providing proof for “Dapsone” resistance.

Later in the 1970s, a Multi Drug Treatment (MDT) was finally found. The MDT itself is characteristically bacteriostatic and bactericidal which means these agents prevent the growth of bacteria and kill it within 24 hours after the first dose of treatment. So 24 hours after his first treatment dose a patient is no longer contagious. This is the reason why children can attend public school after their treatment. Patients need to be treated with a daily dose of MDT from 6 months to one year depending on the Skin Slit Smear Tests result, though complications and wounds that have already occurred before the treatment was started are difficult to cure. In their younger age, a number of patients that were successfully cured were encouraged to work as medical assistants in the centre itself, looking after patients’ wounds or supporting the centre healthcare workers in other ways.

|

|

Today, the settlement is on the tentative list for the UNESCO World Heritage nomination, but does not get much financial support. Visiting schools, NGOs and exhibitions are spreading education and awareness of the leprosy disease. This is urgently needed since around 180,000 people are being yearly infected with leprosy worldwide.

Dori Levai and Caroline Amberg

|